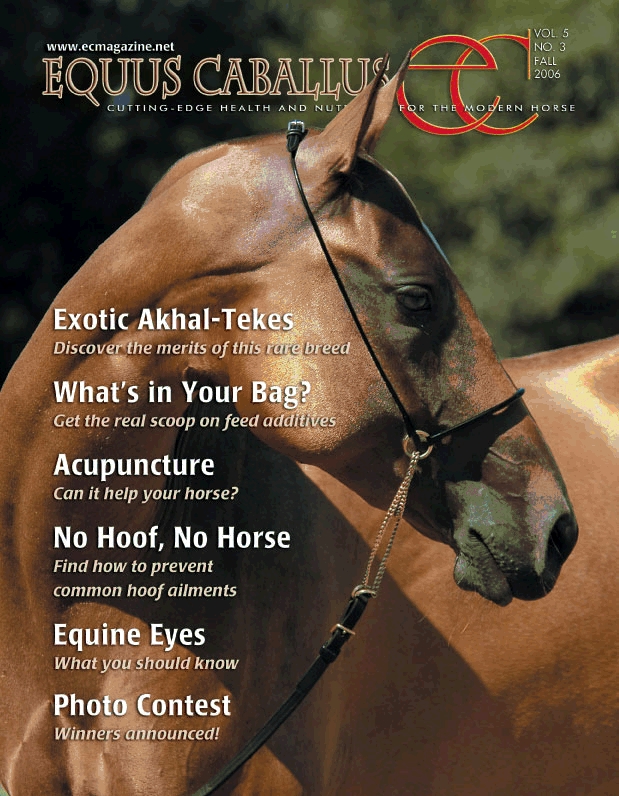

Akhal-Tekes: Gift from the Desert

Exotic looks, graceful moverment and unmatched stamina

best describe this ancient breed.

By Georgia Brown |

| The Akhal-Teke is a tall, refined breed that has been bred for racing and stamina for three centuries by Turkmen nomads of central Asia. Its origins can be traced to Persian civilizations through excavations of skeletal remains and written accounts that have emerged out of the mists of antiquity. Its common ancestors bore a succession of different names: Massaget, Parthian, Nisean, Turkmene, and finally in the 1880s, the name Akhal-Teke was coined. “Akhal” refers to the long oasis that stretches along the northern side of Kopet Dag Mountains. “Akhal-Teke” refers to the horses’ breeders – a Turkmen tribe of nomadic warriors living on the edge of the desert in the foothills of the Kopet Dag Mountains, which today divide Turkmenistan from northern Iran and Afghanistan. |

A History of the Breed

A good horse has always been a source of pride to Turkmen owners. Able to carry heavy loads and travel long distances, often with two riders, the Akhal-Teke was a valuable part of the nomadic peoples who lived in dome-shaped felt tents. They were tethered individually or in small herds near the homes of their owners, and today one of their enduring qualities is the ability to bond with their human partners. |

Scholars studying writings by Roman historians concluded that the pure strains were cultivated to improve and influence several modern breeds throughout the world including the Arabian and English Thoroughbred. |

The harsh geography of Turkmenistan—90 percent is desert on the eastern bank of the Caspian Sea—contributed to the breed’s ability to tolerate heat and drought. With fresh grass available only part of the year, the horses learned to survive on meager rations low in bulk and high in protein. |

Akhal-Teke horses were prized as military mounts and were sent as gifts from Turkmenistan to the czars of Russia in the 19th century. The first official Akhal-Teke stud was founded near Ashkhabad in the 1880s shortly after Russia annexed Turkmenistan.

In the 20th century, an unsuccessful experiment by Russians to improve the breed and increase its size through crossbreeding to English Thoroughbreds ended with the famous 1935 Ashkhabad to Moscow endurance race. The Akhal-Teke proved its superiority by traveling 2,600 miles over terrain that included swamps, rugged rocky soil and three days of scorching sun across the Kara Kum desert. After 84 days, the Akhal-Teke horses arrived in significantly better shape than others. |

Traditionally, Akhal-Teke stallions are taught to rear on command. This is to demonstrate to mare owners that their studs are not only beautiful and successful, but bold, and capable of the demands of war. Today, this tradition can be seen in Russian circuses with more than 10 golden stallions rearing at once! |

During some perilous years under USSR state supervision, distinguished individuals stepped up to defend the breed whenever it was threatened. Horse breeds were depleted in great numbers during the Soviet Union’s mid-century transformation to a machine-driven agricultural economy. An order requiring horses be slaughtered for meat was refused by Turkmenistan horsemen. However, personal ownership of a horse was prohibited, and all horses belonged to government-managed stud farms. Horses were sold only at state auctions and were not chosen by the breeder but by government officials.

With the dissolution of the USSR in 1991, state-breeding farms gradually became privatized. With Perestroika, Russians could own horses, but initially few could afford them. In the first 10 years of the free market economy, many breeders marketed to the West. Some state farms exported horses or set up shareholding companies. As the internal economy grew, the market for Tekes began flourishing inside Russia. Today in Russia, records are carefully maintained by the International Association of Akhal-Teke Breeding (MAAK), and horses bred in Turkmenistan and Russia are performance tested on the racetrack. They also use purebred Akhal-Tekes to improve Budyonny, Karabair, Orlov-Rostopchin and modern Russian Warmbloods. |

Breed Characteristic Type

The breed standard for conformation is different from other horses. The proud carriage of the dry head, distinguished by thin, well-set ears and large and often slanted eyes is described as the “look of eagles.” The straight or convex head meets the neck at an acute angle. The back is long, well-muscled and slopes to a low set tail.

The Akhal Teke is known for its fine coat and a variety of colors ranging from cream to black; some chestnuts, buckskins and palominos have a unique golden or metallic sheen, and there is a silver luster on some grays. It appears like a glossy polish overlaying the basic coat color. (Could this be the horse of a different color in the Oz books?) In 1956, the Russians presented a golden dun stallion to Queen Elizabeth II. As the story goes, the queen’s horsemen thought the gleaming coat was the result of glitter, which they tried to wash off when they got back to the stable. To their surprise, the metallic sheen only increased when their coats were clean.

|

Sign of Success: Neck bands are awarded to stallions for exceptional performance. Originally, neck bands were given after a successful war campaign, attack on a camel caravan or a win on the race track. |

The Path to Florida

There are only a few thousand of these horses in the world and about 250 in the United States. At two farms in Florida, two women are following their lifelong passion to preserve the Tekes’ pure bloodlines and tell others the intriguing story of the breed.

Now living near Sarasota, Dasha Cole grew up in Uzbekistan, and at age 12 she was allowed to ride Tekes at a state-run stud farm and racing facility in USSR. “In those days it was possible to give the grooms a little money, and they would let you ride the older horses. Once you proved yourself capable of riding in the arena, they would let you ride them out to the racetrack,” said Dasha. “I knew then that I wanted to own one someday.”

Dasha got her childhood wish and now owns three Tekes and a small farm in Myakka City. She boards horses and finds time to take dressage lessons on her mare when not working as a realtor in Sarasota. |

“I worked as an interpreter in Russia at high level meetings between foreign dignitaries. When I moved to the US, I set another goal: to compete with my horses in dressage and to make new friends while I show what the Akhal-Teke can do. Through my horses, I hope to bring a better understanding between Americans and Russians so that we can put aside our differences and be friends,” said Dasha. |

Historically bred for racing and war mounts, today, Akhal-Tekes are primarily used for dressage, endurance, show jumping and eventing. |

| Jessica Eile-Keith was born on the Swedish island that is home to the Gotland pony. She first saw a golden Akhal-Teke in a picture book her grandmother gave her and later learned about them through her mother who taught Russian at the Royal Institute of Technology in Sweden. “It became my childhood dream to buy a golden Teke stallion from Russia and ride it to Sweden,” she says. Instead she was instrumental in introducing the breed to Sweden and is past president of the Swedish Akhal-Teke Association. She met an American student, Todd Keith, in Stockholm, married, and when the family moved to Dade City, they brought several of their Tekes from Sweden with them. |

“In Russia today their successes are in endurance racing, dressage, show jumping and eventing,” said Jessica. “They are also gaining popularity as all-around sport horses in Sweden. These horses are often given as gifts to Western heads of state by the Russians. Now they are status symbols; to wealthy Russians, owning a Teke is as important as owning a Mercedes.” |

Akhal-Tekes are sensitive and known to develop a strong bond with their owners; Rosanna and her trainer, Portia Winters, are living proof. |

Thanks to advocates like Dasha and Jessica, the Akhal Teke enjoys growing popularity outside of its traditional homeland of Turkmenistan and neighboring Russia. In Germany, France, Italy, Switzerland and Sweden, they compete in endurance racing, dressage, show jumping and eventing. The Akhal-Teke’s high head carriage and smooth gaits make them stand out under saddle. Their movement appears long, free flowing and elastic, giving the impression of light, effortless agility.

“The breed as a type is a hotblood like the Arabian and Thoroughbred,” said Jessica. “However, in temperament they are social, easy to work with and have a willingness to please.” Heads up competitors. That combination sounds like a winner. |

| Akhal-Teke Conformation |

|

Body: The breed is distinguished by its tall, light and athletic body, standing 15 to 16 hands. Its long, slim body is tubular, well-muscled and slopes to a low-set, sparse tail.

Withers: high, long and well-muscled

Shoulder: long, slanted, with well-developed muscles

Croup: broad with well-developed muscles stretching to the hock

Head and Neck: The long and high set neck gives it a proud carriage. The head is light and dry with a lean lower jaw, usually straight or with a convex forehead. The ears are thin, mobile and high-set on a wide poll. The head is set onto the neck at an acute angle. The eyes are large with a somewhat slanting shape, which is sometimes compared to the look of a bird of prey.

Legs: lean and long with well-developed joints, firm and well-shown tendons, small and strongly built hooves. Legs stand parallel to each other.

Coat: thin and silky with a light mane and tail. The forelock and feather are absent or insignificant.

Colors: range from black to cream in great varieties, often with metallic shine of gold or silver. |

|

|

|

- How to Pronounce:

Ah-cull Tek-y

- The akhal teke horse is the center of the Turkmenistan Coat of arms.

| |

|

- One of the most famous representatives of the breed is Absent, a black stallion who won a gold medal for the Russians in individual dressage at the 1960 Olympics with an astonishing score of 82.4%. The horse went on to compete in three more Olympic games winning six medals under three different riders.

|

|

|

|